Who We Are

Who They Are

Who You Are

Get Connected

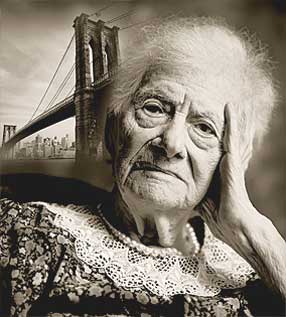

Anna DiFelice

b. March 10, 1892

Montepagano, Italy

Each time I have set off to photograph someone for this book, I have tried to stay in the present, to observe and not to judge. My casual view of their current surroundings rarely has given me any insight into the histories of these hidden supercentenarians. As I drove through the homogenized landscape of gas stations and chain stores in America, the predictable fast-food outlets and the standardized care facilities never prepared me for the diversity and individuality of the elders I encountered. Like delicate time capsules, they held reserves of cherished memories of a world long past.

Each time I have set off to photograph someone for this book, I have tried to stay in the present, to observe and not to judge. My casual view of their current surroundings rarely has given me any insight into the histories of these hidden supercentenarians. As I drove through the homogenized landscape of gas stations and chain stores in America, the predictable fast-food outlets and the standardized care facilities never prepared me for the diversity and individuality of the elders I encountered. Like delicate time capsules, they held reserves of cherished memories of a world long past.

In central New Jersey, I found three generations of the DiFelice family gathered together at a Catholic nursing home. The family had given me permission to visit the week before and I rushed to photograph and interview Anna DiFelice. A frail woman, walking slowly but deliberately, Anna entered a sitting room of the care facility on the arm of her daughter. Using short sentences, she spoke to her daughter in Italian. Her voice was soft, often trailing off to a whisper. Her story was difficult to piece together. It was weeks later, actually, when I corresponded with her grandson, that I received a more detailed picture of Anna's life. I find it inspiring that her grandson knew so many details of his grandmother's life and showed such an intense respect for her.

Anna was born in Montepagano, a small, walled, medieval town that sits above the sea in the Abruzzo region of Italy. Montepagano was fortified against the Turkish and Viking pirates, and I am told it retains many of its original charm. Below the walls is the much newer and better-known beach town of Roseto degli Abruzzi, where Anna spent most of her early years growing up. In those days her parents had wheat fields, and olive and mulberry groves that ran to the sea. The mulberry trees were cultivated for feeding silkworms, raw silk being one of three cash crops (along with wheat and olive oil) that were sent to the towns of Como, Lucca, and San Martino to produce the finished goods. Life as the town knew it changed during WWII when the war front went through the town. The German army camped in the olive groves and in the winter cut and burned down the branches for warmth. Much like the book today part of Anna's family property is now a private German beach club. As a young girl, Anna would walk the beach and collect a now extinct mollusk as a breakfast food. Much like the mollusk, her way of life of a century ago is all but extinct.

Like most children of the time Anna did chores, but the heavy work was done by hired help. In addition to general chores around the house, she helped to cook and tended the silkworms, which she found intriguing. She went to school for a few years and learned to read and write. As a young woman she saw a lantern slide show put on in the village. One of the pictures was of the majestic, newly built Brooklyn Bridge. She was so moved by the image that she vowed to see it. When she had enough money, she went by steamer to America to visit her uncle. Later, she traveled to Philadelphia to stay with relatives and remained there because she fell in love with a young man, newly arrived from Italy, who delivered bread to her uncle's house. He courted her and they were engaged within a short time. At the beginning of her married life they lived in a Belgian community in Philadelphia and oddly, she learned French before she learned English. Her married life, however, was much like that of housewives in Montepagano, with her days filled with cooking, making sausage and wine, and preparing game, fish, and vegetables, all brought back by her husband from his many hunting and fishing trips.

Unlike many of the arranged matches of the day, Anna and her husband married for love. She has lived without him since 1958 when he passed away, seemingly a lifetime ago. While for some it is a blessing to live to be a supercentenarian, for others the idea of outliving most of one's immediate family can be a curse. For those few of us who are touched by chance meetings with people like Anna, we are able to see history come alive, through an encounter that bridges our present with a past, bygone view of life. Speaking with Anna, I couldn't help but feel that I was in the presence of the matriarch of the family; the reverence she received was undeniable. I feel certain that Anna's family structure gave her a kind of social sustenance that has allowed her health to endure, and that nurtures her as she had nurtured them.

Click here to view the next supercentenarian's story.© 2009 Earth's Elders